My Wabi-sabi Spoon

Wabi-sabi? When I first heard this term I remember suspicioning it was some relative to the mouth-scorching green stuff that comes with sushi. But it’s not. This is a conceptual expression that I find wonderfully meaningful. In essence, it is the Japanese art of finding beauty in imperfection. It embraces the natural cycle of growth, death, and decay. It reveres authenticity above all else. It celebrates cracks, chips, the apparent wear from use, frayed edges, rust, tarnish, and the like. It is underplayed and modest beauty, steeped in its own history and waiting to be discovered.

The concept of wabi-sabi expressed through a physical article, has given me pause to revisit personal touchstones in perceptual definitions of what is rich? What is successful? What is beautiful?

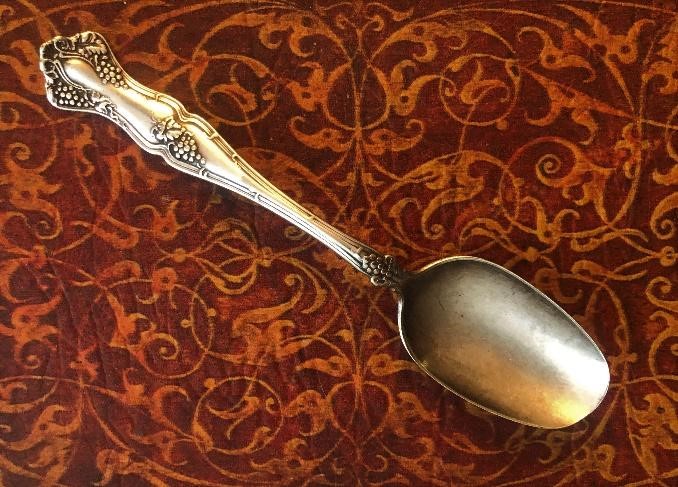

The object I own that wabi-sabi first brings to my mind is an old silver tablespoon that belonged to my maternal grandmother, Hazel Laverne Cooper, whom we grandchildren lovingly referred to as “Munner.” The pattern is called “Vintage.” It has grape bunches, vines, tendrils, and leaves on it,and is my favorite pattern. Yet, it isn’t this spoon’s lovely pattern that provides its main appeal for me, but the wear it shows from the years it spent in my grandmother’s hands—in Munner Cooper’s kitchen.

This spoon was not part of a set, but the only one of its kind in her home,and served as a familiar functional tool. I don’t know where Grandma got the spoon, or remember a time it wasn’t there. Because it was silver she used it to keep glass from breaking when boiling liquid was added to glass cups or jars, or to cool hot coffee or tea, so it was usually sitting out on a kitchen counter.

Munner and the spoon grew in “wabi-sabi-ness” over the many years of her life—the spoon developing scratches, tarnish, and spots worn thin with use—Grandma with wrinkles, stoutness, and silvery hair. They remind me of each other for so many reasons. This tablespoon is a good Rogers Brothers xs triple silver spoon, made in about 1904. The luster of the silver remains quite visible on the high places within its splendid pattern. Grandma was “minted” November third, 1901–and those twinkling eyes and that merry smile never lost their luster during her earthly life and remain etched in my mind’s eye for as long as I will live.

Grandma and the spoon took up jobs seemingly beyond their intended purposes. No more lying on linen napkins with its Vintage cocktail fork or butter knife—no lace tablecloths, and dainty dips in the lobster bisque for this pretty spoon. It was stirring the syrup for the canning of apricots, mixing in the rennet to make the goat’s cheese, creaming the shortening for those oatmeal cookies that delighted so many grandchildren. Heaven alone knows how many functions it served over the years, enough to have worn the tip completely off. I’m kind of amazed it didn’t dissolve completely away from the stirring of coffee alone. Surely a brew that strong must have corrosive properties. Thick as mud and black as overused motor oil—just the way she and Grandpa, and much of Europe, prefer it. Ptui!

Like the spoon, Grandma left her familiars and set out for Southern California in the 1920s—she from Ohio, the spoon from Connecticut. With five little ones born over seven years, Munner and Grandpa, Pop Cooper, made good use of their Richland Farms acre. Pop worked forty hours a week as a pattern maker for machine parts, and Munner kept the home and grounds. She planted, hoed, picked, plucked, washed, cooked, canned, butchered, milked, scythed hay, baked, boiled, and fried. She crushed grapes for the making of wine, and juiced fruits for jellies. She could turn out a perfect pie crust, and shucked corn, peas, and lima beans with astonishing speed. She would scrape the pork hides and render them down into chicharones and lard, cut and wrap the remainder of the porker for the freezer, then grind the meat scraps for sausages. She darned, mended, ironed, and boiled her whites over an open fire in their courtyard, and washed the rest of the clothes in her old hand cranked wringer washer. She fed the chickens, cow, goats, pigs, dogs, and a whole lot of children and grandchildren. By 4:30 every weekday morning she was stoking the fireplace, packing Pop’s lunch, and preparing their breakfast. She said that was their special time to be alone together at the beginning of each new day; and you know that spoon was there.

While her formal education was minimal, as was the norm for girls of her era, Hazel Laverne Crum was primed with more genteel womanly arts. She was taught to crochet, embroider, sew, and play the piano—along with the functional necessities of wifely expectations.

Over the years I think I saw her do everything but complain.

In all this efficiency, she remained cheerful, and epitomized kindness and patience. Munner made all of us feel so cared for and loved—and somehow brought dignity—a wealth of tarnished class if you will, to whatever she invested herself in.

When Rogers Brothers designed my grandmother’s spoon, they thought of function, but clothed it with the Vintage pattern. When my grandmother clothed herself, it was in Vintage Munner. Her chosen ornamentations were always a cotton housedress, and full bibbed apron—appointed with a pair of crew-socks, folded at the ankle, and a pair of sturdy hard-worn lace-up shoes for the yard, or soft shabby slip-ons for the house. This was nicely set off with her coiffure, which, by the time I came on the scene, was a long silver mane, rolled deftly toward the back in a way that framed her face. I used to love to watch her comb her long silver hair and sweep it into its familiar classic style. I remember the day Munner’s three middle-aged daughters decided it would be much nicer if she would cut that hair (“no one over 30 should wear long hair,” they said). So it was cropped and permed. To my eye she lost more than her hair—it was like Samson and the Philistines. They didn’t respect the power and agelessness of “Vintage Munner.”

Like the Rogers Brothers, Grandma did understand the fundamental necessities of pleasure, joy, and beauty, amid the need for functional usefulness. Her famous Dahlias, some as big as dinner plates, stood in a row in front of the massive gardens that fed the family. In front of the dahlias was the great lawn-cum-“sports field.” It was a volleyball court, badminton and croquet field, as well as a picnicking, sack race, and egg toss green with a horseshoe pitch and a broad crabapple tree for shaded lounging. Munner and Pop would bring a measure of fun even to the task of raising the crops, by gardening competitively, seeing who could grow the biggest tomato or pumpkin.

Just like Grandma’s Vintage spoon, years wore away at the tip. A life-long diabetic, the progression took its toll. As her vision left her a bit at a time, she continued to extend loving hospitality, delivering smiles, homemade pie, and English tea on swollen ulcerated feet. I remember when the time came, we had to inspect the plates she so graciously served up—and quietly remove the bits she could no longer see to clean off during their washings.

Too soon she spent most of her time in a wheelchair, which she referred to as “my chariot.” Her heart, arms, and lap were never-the-less kept full—her little dog, a great-grandbaby to rock—and still, she tried to serve. I was there one day when she was yet able to prepare Jell-O. She rolled her “chariot” to the freezer to add ice cubes from a bag she kept there—but, blind, instead poured in frozen Tater Tots. Comi-tragedy—she chose to be amused, but didn’t throw it out. Strawberry potato Jello-O—Mmmmm-mm!

I notice a profound something else in Munner’s wabi-sabi spoon. That it is not a knife or a fork—it is a beautiful and useful spoon. My Grandma was like that—and I fear that, as modern women, we have sometimes been coerced into thinking of spoons as JUST spoons—service pieces, if you will. In moving away to reinvent ourselves as a knife or a fork, we too often lose sight of the great feminine in our concepts of “Feminisms.” We don’t know what to do with our “spoonliness.” Do we hang it on the wall in heels, a push-up bra, and a brooch, as a showpiece? Do we stab, saw, and poke with our smooth rounded edges? Are we persuaded that personal power and purpose of value is to be found only through tools that cut or pierce? Do we fear that daily service will mean being stationed in the back of life’s great silverware drawer? No matter what else I choose to be or not to be in my life, I am encouraged by the life of my grandmother to embrace that part of myself that is a useful spoon. One that finds Munner’s joy, grace, and dignity in raising warm nurturing soups to the mouths of hungry friends, our kin, and our children.

Like the beauty that shines through the tarnish and wear on Munner’s old spoon, the light of her being has shined through the time and lives of all of us who were so blessed as to be loved by her—and will shine forward through us, by way of that love, to our children—and beyond. I inherited this old spoon from my Grandmother. It is my profound aspiration to find and nurture her part in myself—to be even half the woman, the emissary of genuine love. That would surely be an inheritance of untarnishable riches, success, and beauty.

Shine through—shine on, yesterday, today, and forever. It’s true, a great classic never dies.

Radiant now beyond the manufacturer’s

wildest dreams.

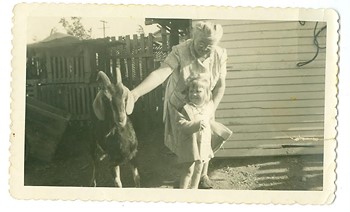

Munner and her three youngest children

(The one on the fence is my mother.)

The squeaking wheel gets the grease—but it’s the first one to be replaced.

In marriage each has to give their 75%.

When your man leaves the house make sure there’s nothing stiff but his collar.

Do draw a line in the sand—but draw it very low, and don’t cross it.

Everything that will ever love you back, poops.

A wise man learns from his mistakes. A fool will learn no other way. [1]

Author Statement: Susan Christen is an Oceanside resident and serial student at MiraCosta since 2009.